South Africa not ready to lower voting age to 16 say the experts

Experts weigh in on whether or not South Africa should follow suit in lowering the voters age.

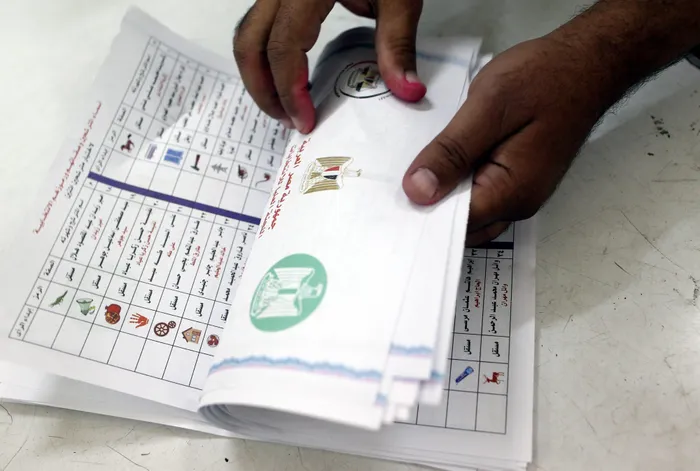

Image: File

The United Kingdom’s announcement that it will lower the voting age to 16 ahead of its next general election has stirred fresh debate in South Africa, where experts warn the country is not ready to follow suit, as it prepares for the 2026 South African Municipal Elections.

According to a BBC report, the UK proposal is part of a broader reform package.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer defended the changes, saying young people who “pay in” to the system deserve to have a say in how their money is spent.

But the decision has drawn mixed reactions. UK Conservative MP Paul Holmes criticised the timing, arguing that there will be no parliamentary scrutiny until September due to the recess, and called the proposal “hopelessly confused”.

Public reaction has been just as divided. While some young people welcomed the opportunity to shape their future, others cautioned that the move could backfire. The UK proposals still need to pass parliamentary scrutiny before becoming law.

In South Africa, where only 18% of registered voters were between the ages of 18 and 30 in 2023, despite two-thirds of the population being under 35.

Political analyst Nkosikhulule Nyembezi believes the country is far from ready for such a shift.

“47% of young people were not interested in voting in the May 2024 elections due to perceptions that their individual vote would not make any difference in the outcomes of the elections,” said Nyembezi.

“However, 53% still believed in the importance of voting as a duty of citizens.”

He cautioned: “Not yet. Under 18s must practise voting in education and social settings such as when voting for student representatives.

“Civic and voter education could empower the 16-year-olds to make political choices,” he added. “However, it will be a long way before they develop the capacity to discharge the corresponding responsibilities of voters.”

According to Nyembezi, civic education in South Africa remains underfunded.

“By allocating resources towards intensifying massive civic and voter education campaigns, we can better prepare young people to take part meaningfully in democracy.”

He also warned of a growing political detachment among the younger generation.

“Perhaps the 18-to-25-year-old cohort whose youths were thrown into upheaval by poverty, hunger, inequality, unemployment, crime, corruption, abuse and neglect, HIV epidemic, and Covid-19 pandemic will adopt a set of socio-political assumptions that form a new sort of ideology that does not quite have a name yet.”

This could give rise to what he called “Generation C — HIV-affected, Covid-affected and, for now, strikingly apathetic and conservative.”

He added, “For this micro-generation, social media has served as a crucible where several trends have blended: diminishing trust in political and scientific authorities, anger about neglect, and a preference for social media influence over parental guidance.”

Despite these concerns, Nyembezi supports the rise of youth candidacy and the growing presence of independent candidates.

“This highlighted that the right to free speech served not only the speaker’s interest, but also the audience’s, in order to make informed choices.”

His advice? “It might be better to focus on getting 16-year-olds to register on the voters’ roll and know their voting rights in preparation for when they turn 18.”

Professor Amanda Gouws, a political scientist at Stellenbosch University, echoed similar concerns, warning that lowering the voting age without the foundation of civic education.

“I am against the idea. There needs to be proper civic education first, otherwise we’re just creating more disillusionment.

“I don’t think South Africa should follow this trend. We already do very little when it comes to civic education and how the democratic system works. Until that is addressed, lowering the voting age is problematic.”

Gouws said she believes lowering the voting age without proper civic education will also open the door for manipulation.

“It can also be easily manipulated by political parties. If we look at past elections, the 18–25 age group already has the lowest registration and participation rates. I don’t see how lowering the age to 16 is going to improve that.

“If this is done, it’s not being done to empower young people, it's being done for cynical reasons, to increase party support. Most young people in that age group are a-partisan; they’re not deeply engaged in politics.

“You can’t expect a 16-year-old to vote responsibly without having a solid understanding of how democracy works. This needs to be built into the school curriculum. As political scientists, we’ve tried to engage with the government about including civic education, but there’s no interest.”

Gouws explained the complexity around understanding politics.

“This is not Life Orientation, civic education is specifically about teaching young people how democracy and politics function: the three tiers of government, how people are elected, how a bill becomes an act, what portfolio committees do.

These are the technical elements that help inform voting choices.

“The quality of a democracy improves when more people are educated and involved. It teaches an understanding of accountability. But it has to start at the foundation. Politics is not intuitive or self-explanatory. It must be taught.”

She said there are also practical concerns like the cost included on expanding the voters' roll while many may not show up to vote.

“To register, you need an ID and that brings Home Affairs into the picture. It’s a domino effect, and if we’re going to talk about lowering the voting age, we also need to talk about the age at which candidates can stand for Parliament, it’s just not viable,” she concluded.

tracy-lynn.ruiters@inl.co.za