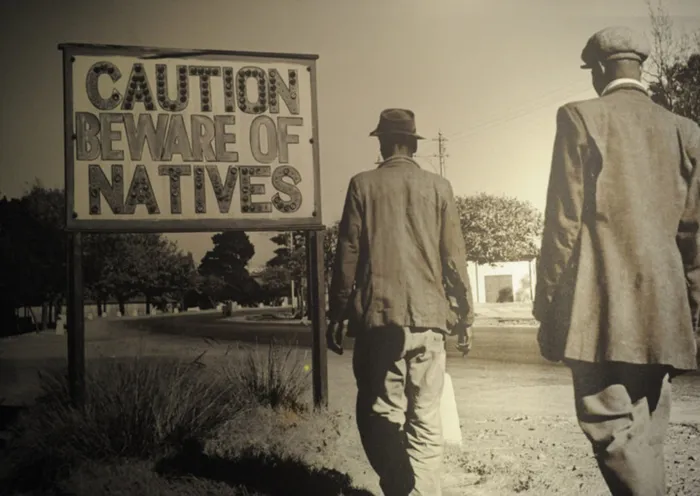

This image is in the Nelson Mandela section at the Iziko Slave Lodge Museum in Cape Town. Slavery persisted until Brazil’s plantation economy could no longer sustain it, making Brazil the last country in the Americas to abolish the system in 1888.

Image: File/Independent Newspapers

THE reason for the Great Trek is also not fully explained. Indeed, the British abolished slavery through the 1807 Slavery Act, which made the buying and selling of enslaved people illegal within the British Empire, but did not end the practice of slavery.

It must be noted that this was not an act of altruism from the heartless Empire, but rather a calculated political and economic manoeuvre. Britain acted less out of morality than necessity, facing revolts by enslaved Africans in the Caribbean (as in French Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti) and an economic shift that favoured wage labour over slavery.

Britain’s supposed humanitarian triumph was riddled with contradictions. While it prided itself on banning the slave trade within its empire, it did not stop slave ships from leaving ports such as Delagoa Bay for another 50 or so years, underscoring the selective and self-serving nature of imperial reform. When Britain outlawed Brazil’s transatlantic slave trade with the Aberdeen Act of 1845, plantations faced a labour shortage soon filled by European immigrants, who enjoyed freedoms denied to enslaved Africans.

Slavery persisted until Brazil’s plantation economy could no longer sustain it, making Brazil the last country in the Americas to abolish the system in 1888. Its legacy was immense; nearly half of all enslaved Africans brought across the Atlantic arrived in Brazil. The final known slave ship is reported to have docked in Rio de Janeiro in 1852, at least according to “official” records.

However, trafficking is believed to have continued for several years after, highlighting the gap between legal abolition and lived reality. Even after formal emancipation in the United States in 1865, systems of unfree labour persisted well into the 20th century.

For the settler communities at the Cape, it is claimed that the emancipation process was deeply resented. Slave-owners received compensation from the British government, but this was payable in London, leaving most Boer farmers unable to access it. Many sources note that, alongside resentment over English law, language and culture and frustration with frontier policies toward African communities, the abolition of slavery served as a key symbolic catalyst for the Great Trek.

Trafficking is believed to have continued for several years after, highlighting the gap between legal abolition and lived reality. Even after formal emancipation in the United States in 1865, systems of unfree labour persisted well into the 20th century.

Image: Supplied

It is plausible that the ban on slave ownership may have triggered the Great Trek. Still, this explanation alone fails to capture the broader dynamics of Southern Africa’s lucrative slave economy. Slavery had long been deeply embedded in the region’s agricultural and frontier systems, generating wealth and structuring social hierarchies.

The sudden disruption of this system affected not only individual farmers but also the very fabric of colonial society, altering power relations and economic dependencies across the Cape and beyond. The broader context of Southern Africa’s slave networks further illuminates these tensions.

Delagoa Bay, for example, served as the principal hub of the regional slave trade, functioning as a bustling centre of commerce and human trafficking, a veritable Johannesburg of its time, until the discovery of gold and diamonds in the Witwatersrand shifted economic activity inland. Slave traders, local elites and frontier farmers were all implicated in this system, which tied the Cape to broader Atlantic and Indian Ocean trade networks.

There is a disturbing view that slavery never impacted South Africa, and that local kings or aristocracy were never involved in this heinous activity. However, historical evidence points strongly to the contrary. Several compelling factors demonstrate that the region was intimately connected to the slave trade and that local elites were often complicit, whether through coercion, taxation, or participation in the capture and sale of captives.

First, South Africa is located along one of the busiest and warmest maritime routes in the world, its coastlines historically hosting dense populations and active trade networks. These conditions made it a natural corridor for the movement of people and goods, similar to regions like the Gulf of Guinea or the Mombasa coast, which were notorious for supplying slaves to global markets.

Actually, there were more slaves (over centuries) taken to the east than to the Americas: Arab countries, India, Iran, Pakistan and Indian Ocean islands have sizeable populations of African descent. Archaeological evidence in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape also points to early interactions between Europeans and local populations.

Second, the northern frontier, stretching from Tzaneen to Durban, lies in proximity to Delagoa Bay, a central hub of the regional slave trade. Delagoa Bay served as a gateway for traffickers who sourced captives from the interior and transported them to both local markets and distant plantations abroad. This geographic reality meant that even communities far from the coast were implicated in the capture, trade or displacement of enslaved people.

The combination of strategic location, dense populations, and active local participation underscores that South Africa was not peripheral to the transatlantic and Indian Ocean slave networks but was deeply entangled in their economic and social systems. Dingane’s attack on Lourenço Marques (today Maputo) in 1833 is always taken out of context and misconstrued as part of the “Zulu expansion”, but this is an attempt to minimise the underlying reasons behind the attack.

In reality, Dingane’s actions were shaped by economic, political and social pressures, including control over trade routes, tensions with European settlers and changes in the slave and ivory trades. The attack demonstrates how indigenous polities were entangled in and responded to pressures from both local and global economic systems, rather than merely seeking territorial expansion. In the midst of all of this, the slave business continued to thrive, attracting Boer settlers who were also eager to gain their share in the trade of persons.

Boers were not mere intermediaries; by buying, selling, and retaining enslaved workers, they sustained their farms, consolidated wealth, and reinforced regional patterns of exploitation, embedding slavery as a defining feature of colonial society and its connections to the global economy. They were deeply entwined with broader slave networks, making slavery a central feature of colonial society with lasting social and economic effects.

Boers introduced their localised version of slavery called the “inboekstelsel”, a system of indentured child labour used by Europeans in Southern Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. Originating on the Cape’s Northern Frontier, settlers captured or received native children as apprentices, forcing them to work until adulthood.

Boer trekkers brought the system into the Transvaal in the 1840s, where children were sometimes sold in a trade known as “black ivory”. By 1866, there were around 4 000 inboekelinge, roughly one for every 10 settlers. Perhaps, this is the primary reason why several historians insist slavery never took place in South Africa.

Although legislation set release ages at 25 for males and 21 for females, these laws were often ignored in remote districts. The Dutch Reformed Church briefly condemned the system, only to rescind its resolution. British control between 1877 and 1881 did little to curb it. Scholars such as Elizabeth Eldredge and Fred Morton argue that, despite the abolition of formal slavery, the inboekstelsel allowed white settlers to continue forced labour under another name.

Portugal and Britain were both seafaring powers with extensive maritime networks. Rather than competing to colonise undeveloped regions, they coordinated their overseas ventures, which explains their cooperative approach in territories such as Southern Africa and Brazil. In this system, the transatlantic slave trade was financed in London but executed through Lisbon, reflecting a close commercial and logistical partnership that allowed Portuguese enslavers to operate with impunity.

Nonetheless, this partnership also thrived when the two countries signed the Anglo-Portuguese Convention of 1891, which effectively protected Portuguese interests in the region. This means Portugal was going to play a significant role in the transition from slave trading to mining, facilitating the transition from Delagoa Bay to Witwatersrand. The British Colonial Office declared South Africa the new ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of the British Empire, displacing India as its most important colony.

The export-oriented slave trade declined sharply in the late 1880s, coinciding with the rapid expansion of gold and diamond mining, which demanded large numbers of cheap labourers rather than enslaved people for overseas markets. This economic shift also helps explain why the Brazilian sugarcane industry was effectively sacrificed: the Lei Áurea (Golden Law), passed on 13 May 1888, formally abolished slavery in Brazil (a legacy of the 1845 Aberdeen Act), signalling the end of a system that no longer aligned with the new global economic priorities. Portugal understood this transition very well.

The companies that had previously owned vessels transporting slaves to Brazil, in particular, were repurposed to meet the surging demand for cheap labour in the mines and to acquire land. This is how the British South Africa Company and Companhia do Nyassa (land acquisition), as well as TEBA (now under James Motlatsi) and its predecessors, WENELA (Witwatersrand Native Labour Organisation) and NRC (Native Recruiting Corporation), were established to source inexpensive labour both within and beyond South Africa.

The slain workers in the 2012 Marikana massacre are part of the legacy of the heavy recruitment of men from the Transkei, Zululand, Basutoland, Mozambique and other regions. Nevertheless, enslaved or near-enslaved labour (later termed “cheap labour”) was sourced from British colonies such as Natal, Basutoland and the Transkei; the Boer Republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State; and the broader southern African hinterland.

A group of BaPedi men holds the unenviable record of being the first sent to the depths of the Witwatersrand mines. Other groups, such as the AmaHlubi and BaSotho, were enrolled in the diamond mines of Kimberley, reflecting their status as the property of the Empire.

Competition for labour and control fueled numerous conflicts: the Mzilikazi wars against top enslavers in the Voortrekkers and Griqua, the AmaHlubi insurgency (1873), the Sekhukhune Wars, the Anglo-Zulu War (1879), the two Boer Wars and the Bhambatha Rebellion (1906). All these conflicts culminated in the Union of South Africa in 1910, where the two competing settler groups agreed to co-govern the newly unified territory.

While often portrayed as a British “victory,” this came at enormous cost to African populations (excluding the amazemtiti with their duplicitous 1912 politics), whose subaltern status was entrenched through land dispossession, displacement and continued forced labour.

Many people are unaware that conditions resembling slavery, characterised by poor pay and entrenched Master-and-Servants laws, including bonded labour on farms and in white households, persist to this day. The farming community, now presented as victims of a “genocide,” continues to hold the highest number of local and foreign labourers under oppressive conditions, maintaining paternalistic labour relations.

Human life is treated as disposable: people are evicted from farms when land claims become likely, or, in extreme cases, killed, with their bodies reportedly fed to pigs.

Siyayibanga le economy!

* Siyabonga Hadebe is an independent commentator based in Geneva on socio-economic, political and global matters.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, Independent Media, or IOL.