How genocide perpetrators exploit the legal framework

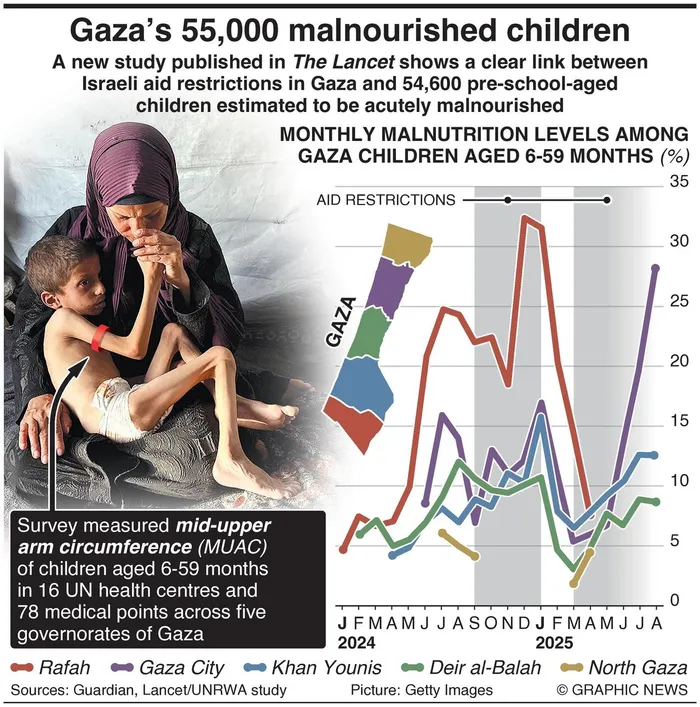

Graphic charts monthly malnutrition levels among children aged 6–59 months in Gaza, since 2024.

Image: Graphic News

THE world watched in horror as Gaza was reduced to rubble. Thousands of civilians have been killed, millions displaced. In the past two years, discussions of genocide have returned to the center of global politics.

Yet in Washington, most politicians have refused to use the infamous G-word, instead speaking only in euphemisms. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and, more recently, Bernie Sanders are two notable exceptions.

The rest of the world has been less squeamish. In 2023, South Africa filed a case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) accusing Israel of genocide. Belize and Bolivia have requested to join. Mexico, Cuba, Egypt, Spain, Ireland, and several others have publicly backed the case.

In August 2024, the International Association of Genocide Scholars accused Israel of committing genocide. A month later, an independent UN commission of inquiry concluded the same.

Despite these developments, international response has been slow if not nearly non-existent. One major reason is that the legal definition of genocide — as set out in the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide — sets an exceptionally high bar for proving what’s known as specific genocidal intent.

Article II defines genocide as certain acts “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Acts alone are not enough; the perpetrator’s mental state must be established to the point that genocidal intent is the “only reasonable inference.”

This standard is understandable in principle — it ensures that genocide, the “crime of crimes” is not applied too loosely. But in practice it has made timely intervention nearly impossible.

Governments that perpetrate mass atrocities are rarely careless enough to leave smoking-gun evidence of their intent. As a result, the world’s collective obligation to prevent genocide has often remained dormant until the killing has reached catastrophic proportions.

This is a design flaw in the Genocide Convention. The international legal order does not require such a demanding standard for analogous domestic crimes. If I am in the process of killing someone, the state may detain me or use force to stop me even before my intent is proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Criminal law also recognises gradations of homicide — from premeditated murder to negligent homicide — so that perpetrators can be held accountable even when their mental state is unknown or ambiguous.

International law lacks an equivalent framework for genocide. The result is that the global community remains reluctant to act until intent is proven beyond a reasonable doubt — even when the destruction of a people is plainly evident.

Imagine that the Allies in WWII knew about the Holocaust much sooner than 1942 but lacked undeniable evidence that Hitler specifically intended to exterminate the Jewish people. Under the current Genocide Convention, the international community would not clearly have had a right and an obligation to intervene on the Jewish community’s behalf.

That seems like the wrong outcome in this hypothetical scenario. Yet, at present, it appears to be exactly how the Genocide Convention would have us react. What’s more, it appears to be exactly what we are witnessing in the current conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

The solution is not simply to lower evidentiary standards for genocide but to rethink how we conceptualise genocide itself. One possibility is to recognize “degrees” of genocide: for instance, distinguishing between “genocide with proven intent” and “genocidal acts.” The latter category could trigger preventive obligations short of full criminal conviction — such as arms embargoes, humanitarian corridors, or peacekeeping deployments — without requiring incontrovertible proof of genocidal intent.

Another option is to adopt a “two-track” system, maintaining the strict intent requirement for criminal prosecutions but allowing state responsibility to attach on a lower standard. This would parallel the way international law distinguishes between individual liability and state responsibility for other atrocities such as war crimes.

Of course, proposals such as these are not without risks. Expanding the definition of genocide could lead to overuse of the term, eroding its gravity and enabling politically-motivated accusations. However, the alternative — leaving entire populations unprotected until their extermination is nearly complete — is arguably much worse. The current legal framework effectively gives perpetrators an incredible amount of leeway so long as they can maintain plausible deniability about their intentions.

The present crisis in the Middle East highlights the urgency of reform. The Genocide Convention was drafted in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, with ex post accountability foremost in mind. Its architects assumed a world in which genocide would be a rare, aberrant crime committed by a defeated regime. Today’s realities are different: genocide and near-genocide now unfold in real time, broadcast live on television and social media, while international institutions remain legally constrained from intervening until it is far too late.

Modernising the Genocide Convention would not be easy. Amending a treaty ratified by more than 150 independent nation-states would require broad diplomatic consensus. But there are reasons for optimism. The UK, Canada, Australia and other countries have now recognised a Palestinian state.

As I mentioned earlier, many states have also backed South Africa’s case against Israel in the ICJ. But more than that, other areas of international law — from trade to climate change — have undergone substantial revision in recent years to reflect new realities.

The prohibition of genocide, arguably the most fundamental of jus cogens norms, seems no less deserving, nor unlikely, especially now, of receiving the same level of attention.

Legal scholars and policymakers should begin serious discussions about whether the Genocide Convention’s evidentiary thresholds and intent requirements remain fit for purpose. At a minimum, the international community needs a framework that enables earlier preventive action — one that does not allow perpetrators to exploit legal technicalities while atrocities continue.

If the international legal order cannot respond effectively when a population is being destroyed before our eyes, it will lose credibility, and it arguably already has. Seventy-six years after the Convention’s adoption, the question is no longer merely historical or theoretical.

If now is not the time to revisit and revise the Genocide Convention, when will be?

Simpson holds a PhD in Philosophy from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He is currently a Research Fellow at North-West University in Potchefstroom.