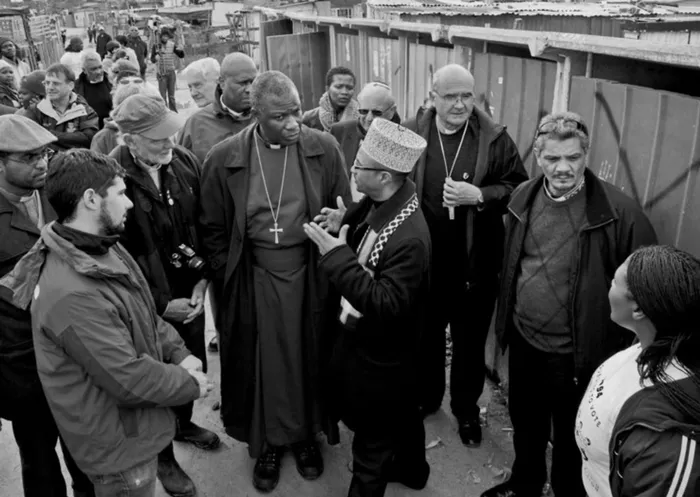

Leaders of a different struggle

Cape Town-110630-Archbishop Thabo Makgoba (in purple robe), Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, leads a delegation from the Western Cape Religious Leaders' Forum (WCRLF) to a number of informal settlements in Khayelitsha, to stand in solidarity with local people suffering from inadequate sanitation. The Social Justice Coalition conducted the visit. Reporter Zara Nicholson, Neo Maditla. Picture Jeffrey Abrahams Cape Town-110630-Archbishop Thabo Makgoba (in purple robe), Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, leads a delegation from the Western Cape Religious Leaders' Forum (WCRLF) to a number of informal settlements in Khayelitsha, to stand in solidarity with local people suffering from inadequate sanitation. The Social Justice Coalition conducted the visit. Reporter Zara Nicholson, Neo Maditla. Picture Jeffrey Abrahams

Gasant Abarder

I grew up in a Muslim household that was more tolerant than most. I knew all the hymns we were taught at school and came home to a mother who encouraged me to sing them because she knew them well too. Growing up we were encouraged to have friends from all walks of life – no matter their background, race or religion. I was acutely aware that my household was different: my friends had very conservative views about mixing with those who were different. Their parents frowned upon it.

I took an interest in religions, particularly Christianity, Islam and Judaism – the three dominant faiths here in the Western Cape. I was fascinated to learn that even though we worshipped Gods of different names and our customs were very different, there was more to keep us together than that which might to hold us apart.

And I was always aware of a tension between the Muslim and Jewish communities locally because of the Middle East conflict. I could not grasp this tension, in light of my own experience of Jewish people that my family and I were in contact with and those who I read about who had made a significant mark in the world. It just didn’t tally.

Later I would of course realise that it was complicated. But that is a story for another day.

To this day I teach my children what my parents taught me: tolerance, respect, understanding. My wife embraced Islam and so our young family celebrates Eid, Easter and Christmas. Our respective families attend each other’s christenings, doepmals, and thikrs (which are Muslim prayer meetings).

It is in this vein that I approach the editing of one of Cape Town’s leading daily newspapers too – the Cape Times.

It is important for this newspaper and the media at large to not only reflect the news of the day but to enrich the debate with different, but also dissident and diverse opinion. We are guided by the South African Press Code which advocates freedom of speech and freedom of expression that is tempered with responsibilities that include limiting harm and providing comment, opinion and analysis that is accurate, unbiased, fair and balanced.

It also binds us to steer away from giving a platform to hate speech, discrimination, bigotry and prejudice and to in turn place a premium on values like tolerance of religious and ideological beliefs.

We are often confronted in our day-to-day work as journalists to make decisions on what is relevant, newsworthy and in the public interest. It is the telling of the South African story – warts and all.

A celebration of all that is right and good but also a fearless critique of our failings, with a relentless role of holding those in power – in government and the private sector – to account.

It is in this space that the interfaith community in our country plays a crucial role as a voice of our collective moral barometer, a guardian of values and social justice. Where does the media fit in? It is a conduit to reflecting this important voice in our democracy. But the only way we as media can do this is if you, the people involved in interfaith movements, remain relevant and address the issues that affront our democracy.

Patience is considered a virtue or cornerstone in most religions. And so the South African faith communities were extremely patient with our fledgling democracy in its early days, taking care not to rush into chastising this young child who had a lot of growing up to do.

But in August 2012, there was a shift in temperature. Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town Thabo Makgoba established an anti-corruption movement and called on the major religions to participate under the auspices of the Western Cape Religious Leaders Forum.

The religious leaders issued a stern warning to political leaders about their reluctance to deal with corruption. They said that the silence of political leaders and the public would lead to society crumbling and warned that the pursuit of money and power was threatening our young democracy.

Makgoba said at the launch in Khayelitsha: “We as religious leaders are still learning to speak truth to power but are afraid to speak truth to our friends who are in power.”

At the same event, Catholic Archbishop Stephen Brislin said that in recent times, corruption had broken the trust between members of the public and their leaders.

Chief Rabbi Warren Goldstein said the moral regeneration of society required that children should learn about the bill of responsibility at schools – that with every right came a responsibility.

And so, a multi-faith anti-corruption movement was born where leaders of different religious persuasions spoke as one. A declaration for the call to end corruption was signed by 18 religious leaders in Cape Town and 44 other signatories.

For very good reason, this powerful statement dominated front pages and news bulletins.

But this was not a new or foreign trend in this country. When South Africa was at its lowest point, at the height of the struggle against apartheid, it was the faith leaders who were an important voice against injustice. Ordinary men and women put their ideological and theological differences aside for the greater good. Some of the biggest heroes of our struggle were Muslims and Jews who fought alongside each other for a free South Africa – just think of Ahmed Kathrada and Denis Goldberg for example. Heroes of the cloth like Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Father Trevor Huddleston, Imam Abdullah Haron.

I believe it is the responsibility of organised religion to continue leading the charge and leading our struggle. But this is a different stuggle.

It is a struggle against poverty, unemployment, corruption, indifference, bigotry, injustice, discrimination, gender violence, women and child abuse, and the apathy many display towards active citizenry. When you as organised religion take up your rightful role and step into the fray, we will do our role as media and report on what you do and say because we won’t be able to ignore your relevance.

And that relevance goes to the heart of every story that shapes our nation or tears it apart. We need the voices of our faith leaders to be the voices of reason and the critical voices when young women like Anene Booysen are raped and murdered, when another child victim is claimed in gang crossfire, when drug abuse becomes so rife that a mother is moved to kill her own son, when mineworkers are gunned down at the hands of our police force, when our road death toll is in danger of breaking new records, when protesters adopt unsavoury and unhygienic ways to voice their dissent, when graft and corruption becomes endemic in public and private life, when we are in danger of buying into the doomsayer’s notion of how we are on the road to being a failed state.

I have always been committed to the idea of an interfaith movement and I believe Cape Town’s interfaith movement is the most vibrant in South Africa and arguably in the world. Very few global cities have the kind of interfaith solidarity and co-existence that we have in Cape Town. It is something that needs to be cherished and celebrated and the media has an important role to play in doing so.

In my previous role as editor of the Cape Argus I was responsible for the publishing of a series of prominent opinion articles in 2012, penned by Interfaith leaders about their aforementioned fight against corruption. In these pieces, clerics like Rashied Omar, Mickey Glass and Makgoba spread the universal message that corruption would no longer be tolerated.

In an article written in 2010 by Imam Rashied Omar, of the Claremont Main Road mosque and current chairman of the Western Cape Religious Leaders Forum, he very astutely summed up the potential and gravitas of the interfaith community. Omar has consistently spread the message that we have strength in our diversity.

Omar writes: “Interreligious dialogue and solidarity has been one of the major beneficiaries of the post-apartheid dispensation. The new non-racial and democratic government under the moral leadership of first president Nelson Mandela has worked hard to sustain and further develop the legacy of interreligious solidarity forged in the struggle against apartheid.

“In response to a call by Mandela, religious leaders have set up an interreligious Forum of Religious Leaders to liaise between government and religious communities. Ironically, however, the post-apartheid South African state’s overt policy of religious pluralism and interreligious harmony has not been sufficiently buttressed by religious leaders at the civil-society level, and consequently it has not sufficiently filtered down to the grassroots. This is an anomaly that interreligious activists in South Africa are aware of and are working hard to correct.

“For me, the litmus test of ‘good’ and “bad” religion is the extent to which we are willing to embrace the ‘other’, whoever that other may be. We need to recognise our common humanity and see others as a reflection of ourselves. If we do not try to ‘know’ the other, how can we ever ‘know’ the divine?”

So what role, does the media play in promoting interfaith harmony?

A central one – because in a way, like the messengers of gospels of the divine word, we are modern day messengers with an obligation to the truth and justice. But our request to you is simple: make yourselves relevant by speaking as one about the issues that shape and define our world.

l Abarder is editor of the Cape Times. This is an edited version of his speech yesterday at the second annual UN World Interfaith Harmony Week Breakfast hosted by the Cape SA Jewish Board of Deputies in Cape Town on the role of media in promoting interfaith harmony.