Inmates can have access to personal computers, other devices for studying, says Concourt

In a unanimous judgment, the court held that the blanket prohibition on personal computers in inmates’ cells infringes the right to education, because inmates cannot access reading material for their studies and complete educational tasks when they are in their cells.

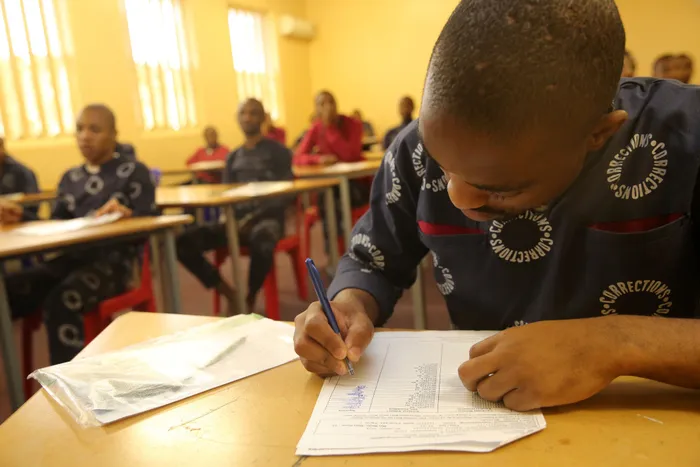

Image: File Picture: Nqobile Mbonambi / Independent Newspapers

THE Department of Correctional Services has been given 12 months to prepare and promulgate a revised policy relating to the use of personal computers in inmates’ cells to further their education.

This after the Constitutional Court dismissed an appeal brought by the Minister of Correctional Services challenging the judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) which ruled in favour of inmate Mbalenhle Sidney Ntuli.

In a unanimous judgment, the court held that the blanket prohibition on personal computers in inmates’ cells infringes the right to education, because inmates cannot access reading material for their studies and complete educational tasks when they are in their cells.

The court held that the right to further education enshrined under section 29(1)(b) of the Constitution plainly encompasses access to textbooks and other tools necessary for fulfilling the right, including electronic tools.

For that right to be effective, education must include adequate learning resources, said the apex court, adding that this is true both inside and outside prison.

“The Policy Procedure Directorate Formal Education, as approved by the second applicant and dated 8 February 2007, is unconstitutional and invalid to the extent that it prohibits the use of personal computers in cells for purposes of further education in circumstances where such use is reasonably required for such further education, and is set aside. The order of constitutional invalidity is suspended for 12 months from the date of this order. The applicant is directed, within 12 months from the date of this order, to prepare and promulgate a revised policy,” the court ruled.

Correctional Services Minister Pieter Groenewald.

Image: Itumeleng English/Independent Newspapers

This case relates to the constitutional validity of a blanket ban imposed by the Department of Correctional Services on the possession and use of computers by inmates in their cells in correctional centres.

The ban emanates from a departmental policy, the Policy Procedures on Formal Education Programmes (Policy), which regulates the use of computers by inmates who have registered for studies and require the use of a computer. The Policy was approved by the Acting Commissioner for Correctional Services on February 8, 2007.

At the time Ntuli was an inmate at Medium C in Johannesburg prison, where he is serving a 20-year sentence. He was registered with the Oxbridge Academy to pursue computer studies with a focus on data processing. He has since passed and graduated. While he was studying he needed to use a computer for his course. He had been transferred to Medium C from the Medium “B” Correctional Centre (Medium B) on July 20, 2018 for undisclosed reasons.

While in Medium B, he was authorised to have and to use a personal desktop computer in his single cell for the purpose of furthering his tertiary education.

However, after his arrival at Medium C, the desktop was taken away and he was told to use the computers in the computer room. The computer room was open from 9am to 12pm. It re-opened at 1pm until 3pm on Mondays to Fridays. It occasionally opened on weekends but never on public holidays. Since every cell in the entire centre is opened at the same time, the centre was exceptionally noisy and studying with many distractions was extremely challenging. His overall complaint was that he was often deprived of sufficient time to study. The department’s objection to Ntuli being allowed use of his computer in his cell was based on the contention that it would create a security threat.

“The applicants’ primary concern was that inmates may smuggle modems into their cells or use illegal cell phones to create hotspots. According to the applicants, inmates are searched on a daily basis, and there are regular security breaches where cell phones or electronic devices are found in the possession of inmates. Illicit possession of a cell phone in and of itself provides the possessor and user access to the internet. They do not need a computer to achieve such access. But there is an even bigger problem for the applicants – not an iota of evidence of incidents manifesting this alleged grave risk was adduced. In sum then, the applicants have failed to put up justification for the limitation of the respondent’s right to further education,” the court held.

Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR) who represented Ntuli welcomed the outcome.

“This is a vindication of our client’s rights who at the end of the day only wanted to further his education and increase his capabilities. We hope no incarcerated student seeking to upskill themselves has to undergo what Mr Ntuli has experienced,” said Head for the LHR Penal Reform and Detention Monitoring Programme, Nabeelah Mia.

The Minister’s office did not respond to requests for comment by deadline.

Cape Times