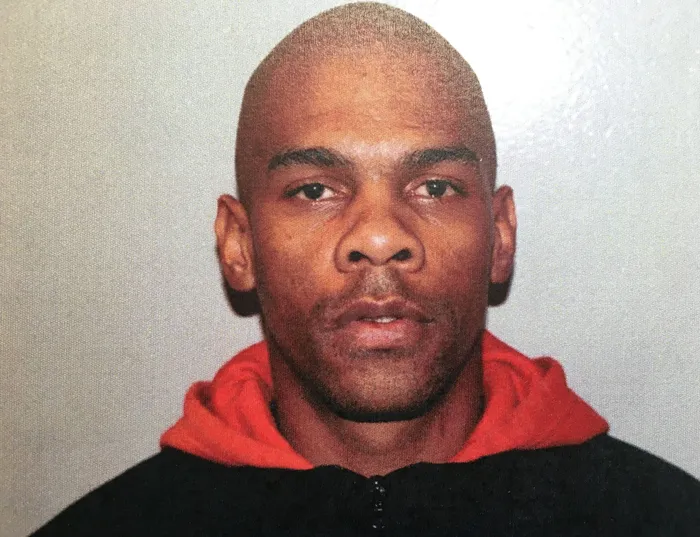

Alfonso Seconds was recently convicted of the murders of two men from his neighbourhood. Picture: Supplied Alfonso Seconds was recently convicted of the murders of two men from his neighbourhood. Picture: Supplied

There are several ways of seeing Alfonso Seconds, also known as “die Eye”, “Fonnie”, “Rasta” or “Storm”.

He is a son distressed by the plight of his mother, a Manenberg man who fancies his own dancing ability, an individual conscious of the influence of “vekere vrinne” (wrong friends), a 28-year-old who can’t read or write.

He is also a one-time seller of tik and mandrax, a gangster and a murderer, having mortally wounded two young men, Warren Williams, alias Mandela, and Faizel Jacobs, alias Scott, in shootings, in April 2015 and in February last year, both in his immediate neighbourhood.

Ranking the facts by any conventional social measure, Seconds emerges, in the idiom, as a “bad character”, a “danger to society”, someone who deserves to be “put away”.

His immediate fate is in the hands of the Western Cape High Court, where he has been convicted for the two murders (among other charges) and is set to be sentenced.

But a telling feature of the trial is a document – “Alfonso Seconds in context: Towards a criminogenic assessment” – crafted by UCT criminologist Elrena van der Spuy, which seeks to place the murderer, as a human being, in a social and personal setting which, she argues, is unignorable.

Bleak evidence in the trial reveals Manenberg, or the worst parts of it, as a society of grim and inescapable, sometimes deadly, intimacy in which despair, drug abuse, violence and criminality seem casually incestuous, an indivisible condition that is commonplace, day and night. Deadly turf wars between the biggest gangs, the Americans and Hard Livings, break out at the slightest provocation, without warning.

At only slightly greater magnification, you sense, Alfonso Seconds would have been visible in the Google Maps satellite image of Manenberg, had he been out in the sunlit streets of his domain when it passed by.

But, zoom in as we may, the limit leaves us suspended at a point just high enough above the notorious suburb to make out merely its drabness and tightly packed form. In the photo taken from space, the patchwork of grey and dun roofs is crammed, haphazardly in places, into an original scheme of fixed dwellings or flats that left plenty of space for the gardens, lawns and trees one might ordinarily expect such a layout to yield. But in this bird’s-eye perspective, Manenberg is a depleted panorama with, here and there, scrappy evidence of a tenacious tree or vine or a stubborn bristling of grass.

A riverine theme – perhaps optimistically – runs through the street naming, all the way from Thames, Plate and Seine to Rio Grande and, a minor South African tributary, Renoster. There are two Renosters, separated by a dense block of dwellings and backyarder shacks; Renoster Rd Grande and Renoster Walk. The latter is our entry point – though in Seconds’s grittier argot, it is “Renosterhok”. He was born, and lived, at number 12a. Renosterhok remains his domicile, the crucible of his vulnerability, the scene of his crimes.

If it is possible to snoop on Renosterhok from the sky, the reality on the ground is far more vivid. This is a core subject of Van der Spuy’s report: “a poor and congested urban space where the overall ‘quality of life’ is bleak” and where “the struggle for economic and social survival is real”.

Manenberg’s 1.79km² is home to 34 760 people in 7 921 households. Just over half – 52% – of households are headed by women. The average annual income is R29 400 (R2 450 a month). A third of the economically active population is employed, 75% of them in the informal sector. Only 45% of school-age children are in school; 58% of the population completed Grade 9 or higher. Schools in Manenberg typically experience low teacher morale, high dropout rates and ill-discipline, factors which “combine with toxic effect with the predatory behaviour of street gangs which infiltrate school grounds”. The safety of residents, on the streets and in their homes, is “compromised”.

“High levels of interpersonal violence result in high rates of victimisation for children, women and men. Gang rivalry results in turf battles which in almost cyclical fashion result in shoot-outs with many casualties.

“Manenberg constitutes one among a number of other impoverished communities on the Cape Flats where the legacies of apartheid (forced removals, economic exclusion, social marginalisation) cast a long shadow over its people. Among youth in particular…there is little of a sense of belonging to and inclusion in the democratic polity.”

Van der Spuy acknowledges recent provincial schemes to “re-imagine” Manenberg, noting soberly: “Suffice to say the provincial plan recognises the challenges are complex.”

In Manenberg – as in other poor Cape Flats communities – a “wide range of problems intersect and conspire in ways which rob citizens of hope for a better future at least within the licit economy”.Typically, such conditions produce “pathways to crime” or “criminal trajectories”.

“Densely populated urban localities characterised by poverty and unemployment create conducive conditions within which criminal careers can be developed… key institutions such as the family and the school system are often dysfunctional. In these kinds of places interpersonal violent crime is rife and substance abuse widespread (and) gangs proliferate and act as surrogate families for young men… (providing) structure, meaning and purpose to youngsters (and) meaningful rites of passage to young men who roam the streets of the ghetto – often fatherless and penniless.”

She then turns her attention to the murderer, in a section titled “A man called Alfonso Seconds”. Her account is the sum of a 90-minute interview with him in the holding cells at the High Court a month ago. The “life history of Alfonso Seconds as told by him” is not, Van der Spuy points out, a verified biography so much as an “oral re-construction of past experiences filtered through perceptions and memories of the world”. His story “is important for the deeper patterns it reveals about a man called Alfonso in a place called Manenberg at a particular point in time”.

In summary, Van der Spuy writes: “Alfonso was born into a large family who lived in a small house in a poor and highly populated area characterised by many social problems. "His mother developed a severe drug dependency early on in his life. There are signs of psychological stress and mental instability in her history.

“His relationship with his maternal parent seems to have been a fraught one. He seemed not to have been a recipient of supportive nurturing and yet he expressed deep attachment to his mother. The household was characterised by conflict. As a child he was subjected to harsh punishment.

"He dropped out of school at a young age. He himself talked of ‘peer contagion’ and hanging out with the wrong crowd.

“Some siblings became involved in the business and networks of gangs. He was sent to an ‘industrial school’ for troublesome kids and so entered yet another institution of control.

“His stepfather – the stable referent point in his life – left the household when Alfonso was at a particularly vulnerable age. Fortunately, the stepfather continued to provide both material and social support.

“Minor infractions brought him into periodic contact with the police. His gainful employment in the business of the stepfather, however, must have instilled a sense of responsibility and self-discipline.

"He was implicated in car theft and stood accused of the crime of murder at another stage. He entered and exited both Pollsmoor and Goodwood prisons. He was shot at and sustained serious injuries. There are signs along the way of increasing entanglement with gangs.” (He is described by witnesses as a Hard Livings member but insists he is a member of the 26 prison gang, not Hard Livings.)

Was he then – the question is a subtitle in Van der Spuy’s report – “An ordinary man in a bad place?”

“On the basis of the evidence before me I conclude the ‘trajectory’ or ‘pathway’ of his life was forged by complex social (family, peer group, school) and structural (poverty, social dislocation) circumstances (associated with “risk” and anti-social rather than “resilience” and prosocial lifestyles).

“In my consultation (with Seconds) I was struck by his deep concern with intimate others in his life (his mother, his younger brother, his stepfather), his acute awareness of the consequences associated with the ‘choices’ he exercised along the way, and a longing – since 2016 – to lead a different kind of life.

“Alfonso Seconds battled considerable adversities in his life. My impression is he did so with a degree of moral consciousness and social responsibility towards others.

"At many times in our conversation he intimated concern about the trajectory of his life. In my conversation with him he has shown good capacity for insight. He is at that stage of his life where he wants to embrace a more prosocial pathway.”

Van der Spuy begins her criminogenic assessment by noting human behaviour “is shaped by a complex mix of factors”, observing not all people growing up in poor or rough neighbourhoods “end up as delinquents or career criminals and not all individuals growing up in comfortable and peaceful middle-class neighbourhoods are morally upright and law-abiding citizens”.

She ends with a subtle segue from particular to general, from “him” to “us”, when she writes in sentencing Seconds, it would “be appropriate” for the court “to acknowledge the circumstances he had to negotiate” for, taking these factors into account, “the court will acknowledge the delicate interplay between the many factors which shape all of our lives”.