10 years later Nkosi’s brave dream lives on

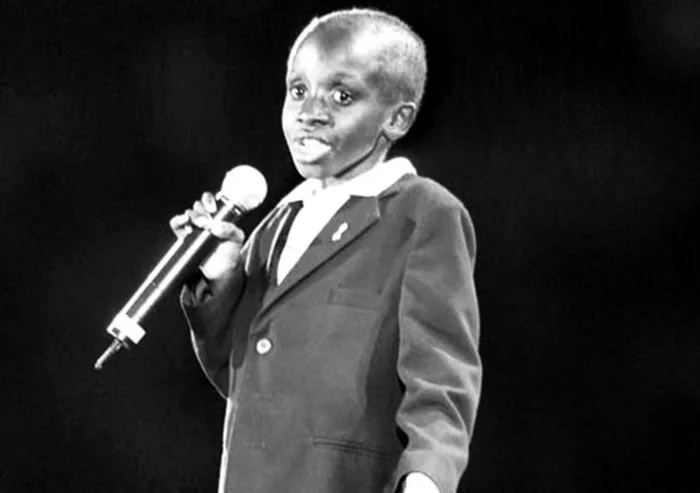

Nkosi Johnson speaks at the 13th International Aids Conference in Durban on July 9, 2000. Picture: AP Nkosi Johnson speaks at the 13th International Aids Conference in Durban on July 9, 2000. Picture: AP

Ten years ago yesterday, South Africa’s longest-surviving child born with HIV at the time, Nkosi Johnson, died at the age of 12.

He became an activist and the face of HIV/Aids in Africa when he prodded government policy that, in 1999, allowed all infected children the right to education.

During a speech he delivered at the 13th World Aids Conference in July 2000, Nkosi challenged the government to roll out antiretroviral (ARV) treatment to pregnant women to prevent the transmission of the virus to their unborn children.

His famous, impassioned “we are all the same” speech pleaded for acceptance of all people infected with HIV.

“I want people to understand about Aids, to be careful and respect Aids. You can’t get Aids if you touch, hug, kiss, hold hands with someone who is infected. Care for us and accept us – we are human beings. We are normal. We have hands. We have feet. We can walk, we can talk, we have needs just like everyone else. Don’t be afraid of us, we are all the same,” he said.

While much within the country’s HIV/Aids landscape and the government’s response to the pandemic has changed in the decade since Nkosi’s passing – including the roll-out of ARVs in 2004 and a policy change to administer ARVs to pregnant women and people co-infected with TB and HIV who have a CD4 count of less than 350 –HIV activists say much more needs to be done.

Statistics from the national HIV and syphilis prevalence survey – which is based on pregnant women receiving antenatal care at public clinics – estimate HIV prevalence in pregnant women to be around 29 percent.

Gail Johnson, Nkosi’s foster mother and director of Nkosi’s Haven, says more focus on counselling for adolescents is needed.

“There is pre- and post-counselling for people testing for HIV, but there’s no sort of therapy in place for children infected from birth, who are now in their late teens and having to confront their status.

“There are issues of anger at being a true innocent victim while they have to put up with peer pressure to become sexually active. What support system is there in place for that age group? Who can they consult with?” she asks.

Today Nkosi’s legacy lives on through Nkosi’s Haven in Berea, Joburg, and Nkosi’s Haven village in Alan Manor, which offers a safe, nurturing home environment for mothers, their children and HIV/Aids orphans.

“Because Nkosi was separated from his mother from a young age, it was his dream to do something to ensure that other children in similar circumstances as he was don’t have to live without their mothers,” Johnson says.

Together the institutions accommodate 188 residents – 42 mothers and 146 children. Half of these children are orphaned.

In 2008, Nkosi’s Haven acquired a farm near Sebokeng that is now being developed into a self-sustaining kibbutz-style community farm to be called Nkosi’s Haven4Life.

Johnson says the intention is to create vegetable gardens and set up a chicken farm that would not only feed residents at all three locations, but also sell surplus crops and products made by the resident mothers. Meanwhile, a movie about Nkosi’s remarkable life is being developed, a co-production between Storyteller Entertainment, Creations Media Group and Keep a Child Alive, with American R&B singer Alicia Keys as one of the executive producers.

Dylan Ben-Israel, producer for Storyteller Entertainment, says he is looking for a scriptwriter. The roles of Johnson, who Naomi Watts was originally scheduled to play, and Nkosi, which will be played by a South African, have not been confirmed yet, but the movie will be shot in the country and proceeds will go to charity.

“The one thing that makes this project special is that we are donating all our back-end profit to charity. This project has always been about getting the movie made, not about getting rich making it.

“What Nkosi achieved in his short life is more than most people achieve in their entire lives, and his story needs to be told to the entire world,” Ben-Israel adds.