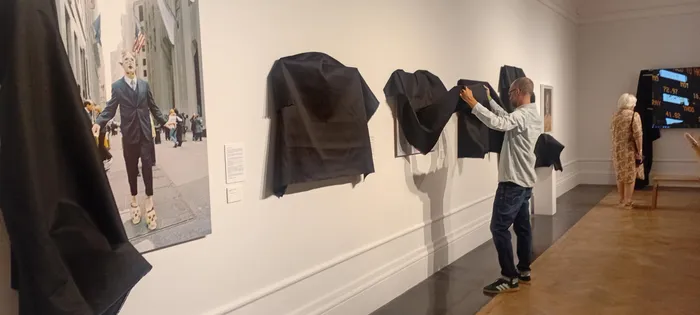

Audience member views Steven Cohen's censored work at Iziko South African National Gallery (ISANG).

Image: Supplied

Exhibition openings aren’t typically remembered for their speeches. But, at last week’s Steven Cohen: Long Life retrospective exhibition opening at Iziko South African National Gallery (ISANG), the remarks alone were enough to pull everyone to the edge of their seats.

Virginia MacKenny, an Associate Professor of Painting at UCT, had just sketched me a quick history of Steven Cohen; including the time, two decades ago, when she gently talked him out of enrolling for a Fine Art degree. “Steven Cohen is a self-taught artist and has already proven themself one of the best performance artists alive! What would a degree do for them?"

Our chat was abruptly halted by a request to take our seats. Then we commenced our descent: Bernedette Muthien, of the Iziko Museums of South Africa Council, expertly walked us through the simmering tension and the gallery’s move to ‘redact’ parts of Steven Cohen’s installation.

“In presenting this exhibition, Iziko Museums of South Africa carries a responsibility to ensure that the works on display align with our institutional values, our ethical commitments and the cultural sensitivities of the communities we serve. After a careful internal review, Iziko has decided not to show a selection of works originally intended for inclusion,” said Muthien before moving on to quote the preamble to South Africa’s Constitution.

A few minutes later, the next speaker, Charl Blignaut, tore up their prepared remarks and spoke off the cuff.

“The museum denies that this is censorship and insists it will not sacrifice human rights for fashion. Fashion!? Steven Cohen’s work has always been about cultural and political resistance. It is rooted in his lived reality as a white, queer, Jewish South African man, his work forces attention onto marginalised bodies, identities and histories that polite society would rather ignore.”

Blignaut went on to detail his life-long friendship with the artist and how the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) almost killed them on a hill. Modelling around Loftus Versfeld rugby field dressed as an “ugly girl” in 1998. The contentious Golgotha performances abroad which were now being reduced to "fashion". Cohen crawling to cast his vote whilst wearing heels made with metre-long gemsbok horns at the 1999 elections. And more.

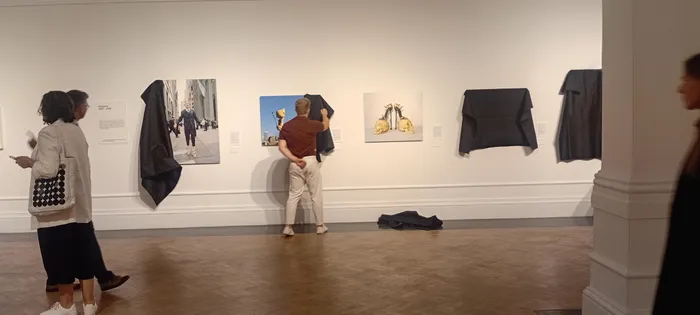

More people viewing censored works.

Image: Supplied

The exhibition’s visibly “discombobulated” curator, Anthea Buys, recounted the 10pm message she’d received the evening before the opening, informing her that the museum had decided to remove certain pieces from the exhibition.

"Following Iziko’s decision, Cohen and I negotiated that we would cover the contested works with cloth instead of removing them, because to remove them would have been to capitulate without discussion, without the possibility of imagining other ways forward together. We wanted to make visible an occlusion, to register disagreement, and to say that we are not afraid of the discomfort that comes from that. In fact, dissensus is symptomatic of a free society. Long Life is a beautiful, moving and life-affirming exhibition because that is what the work is."

It must have been an hour of speeches. By the time we finally entered the gallery, everyone made a beeline for the censored works. Needless to say, people lifted the 15 or so sitting shiva black drapes to peek underneath them. A few pulled them off entirely. Prompting gallery staff to hurry over and cover them again. This became a futile exercise.

One corner of the gallery was left bare, marked only by a single nail and a note that said: “This work has been removed by the lender, against the wishes of the artist. This action responds to Iziko’s decision to remove other pieces from the exhibition.”

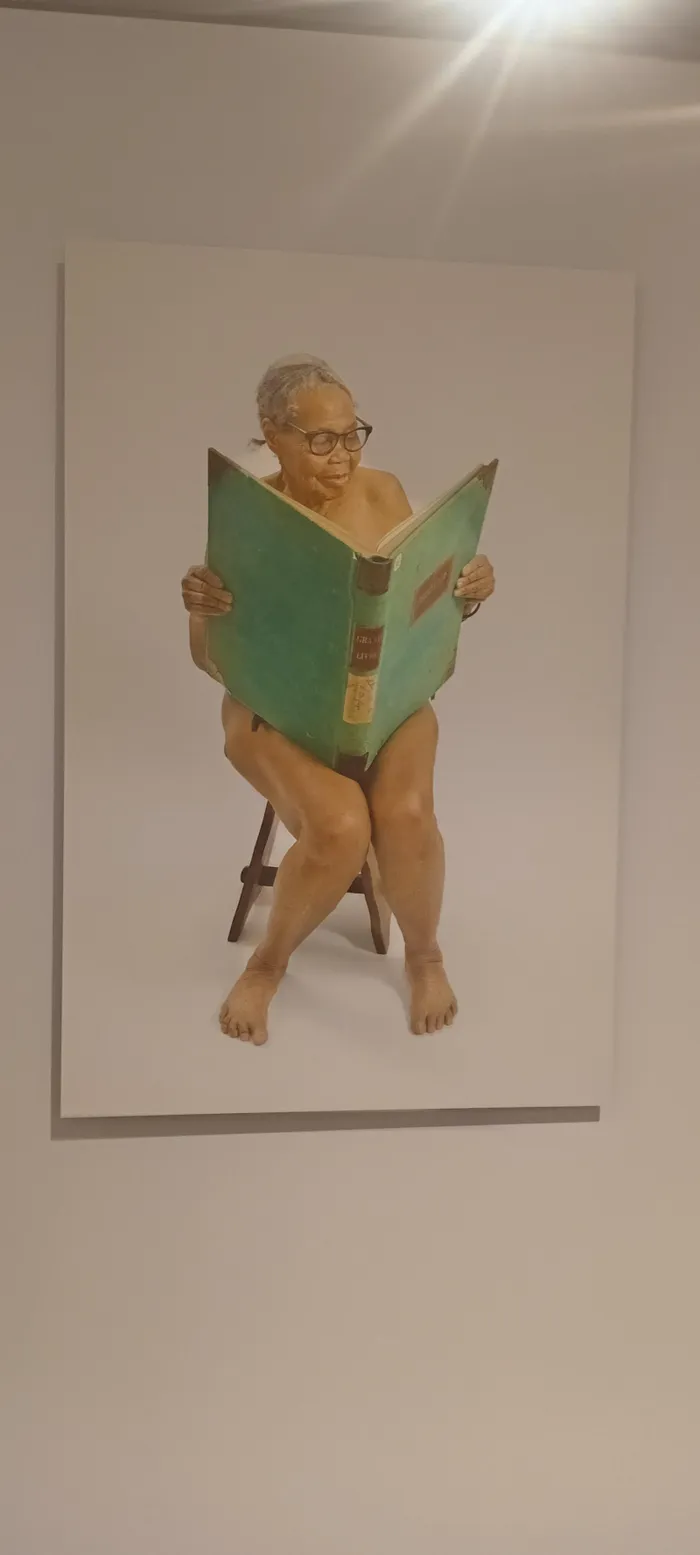

One of the censored Nomsa Dhlamini artworks by Steven Cohen.

Image: Supplied

Problem one: In the Golgotha series, Steven Cohen uses real human skulls as shoes to critique capitalism. In New York’s SoHo, you can legally buy human skulls. Cohen buys them. Walks the streets. Gets arrested. Documents everything. Photos. Videos. The works. ISANG, however, seems unable to grapple with the ethical implications nor the message the artist was hammering home. I mean, what's next? In some countries you can pay for assisted suicide. Is a national public gallery expected to one day accept an artwork that entails an artist heading off to Switzerland and publicly ending their own life on the streets there? All in the name of making a statement on capitalism. So no limits, anything goes with art? Okay.

Problem two: Umam’ uNomsa Dhlamini, Cohen’s family domestic worker since his childhood, "a mother figure and a collaborator" in over forty performances across twenty years. In one of the censored works there is a video, titled “Maid in South Africa” where umam’ uNomsa Dhlamini cleans the artist’s childhood home while engaging in a striptease performance. Bum cheeks exposed. This was a then 70-plus-year-old Swaziland-born woman doing this. ISANG could not wrap its head around this level of (self-)disrespect.

Back in 2007 I wrote a Thought Leader piece on this exact phenomenon. It was the UFS Reitz Four incident back then. Black domestic assistants become absorbed into white families and in the process also pander to their little masters' whims. “Mavis jump!”, Mavis laughs it off with an “usile ke lo mntana!” Yet, Mavis actually has a real life beyond the 'job'; Mavis has a family and is likely deemed a formidable and respected community leader (because she's one of a few with an income in a sea of poverty). No township child would dare say anything offbeat around her. She too would never allow that. Yet, a little master in some suburb pulls Mavis by the nose, day in and day out. Or in the curious case of Cohen, by the panties, day in and day out. Privilege is the inability to see anything wrong with this picture.

This is not to strip umam’ uNomsa Dhlamini’s sense of agency or autonomy. Still, we must acknowledge the context we live in; a country shaped by deep social and historical forces. To miss this is willfully misunderstanding South Africa.

I will not attempt to speak for ISANG but as a government entity I understand where they are coming from. I also understand the artist's intention to take viewers into the world of our collective pain and trauma. The message is loud and clear.

In any other commercial art gallery, I am certain this would fly, but here we are dealing with a public institution still shadowed by its own historical complexities. It’s going to be interesting to see how school tours engage with this exhibition once schools reopen in January. Knowing full well that Cohen's work was once removed from a number of schools in the past. Will this full exhibition actually remain on display until the planned closing date of June 30 next year?

There is much to unpack. However, I must apologize to the artist and curator for committing so much time away from the actual art. On the evening Cohen did not speak but instead performed a moving solo performance in which he sat inside a gigantic gumball machine for two hours flat.

Overall, this is by far one of the best exhibitions I've ever attended. It the recorded performances that I like most. There are many more rooms of art. There are even cabinets with personal artefacts, there are costumes hanging, animals stuffed and being slaughtered, penises, tributes to Elu Kieser adorn walls and more.

As a whole Long Life is about injustice, loss, life, love, death and above all Steven Cohen.

Steven Cohen will have you questioning your entire existence and was once quoted saying: “I am messing with a society that is more shocked by the violence of my self-presentation as a monster/queer/unrepresentable or whatever than by the actual violence they live with every day."

Cape Times

Related Topics: