WATCHING paint dry ultimately becomes a profound experience in Athol Fugard’s life-affirming new play. By opening tins, singing and executing brush strokes, his characters transform into historians and philosophers.

First performed in New York last year, The Painted Rocks at Revolver Creek is the second production that sees the celebrated Tony Award-winning author explore the topic of South African outsider artists (a term he also uses to refer to himself).

The first was in 1984, when he undertook a journey to Helen Martins’ Nieu-Bethesda Owl House in The Road to Mecca. This time around he departs from the Eastern Cape and travels towards the Mpumalanga farm Esperado (at Revolver Creek).

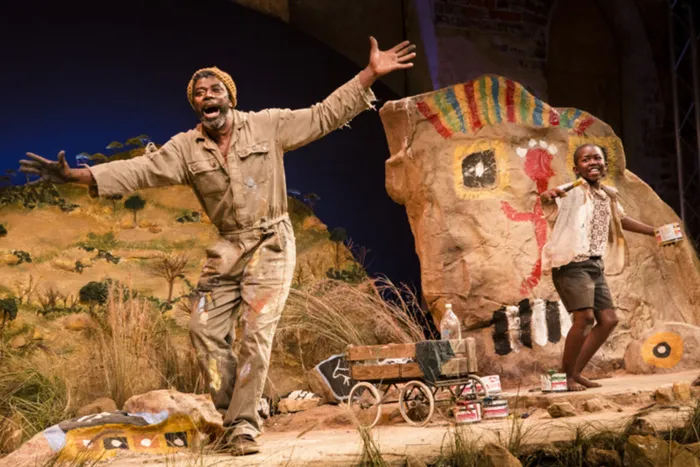

Co-directed by Fugard and Paula Fourie, it is here where the script first introduces the viewer to farm labourer and painter Nukain Mabusa (Sebe). Accompanied by his young assistant Bokkie (Mango and Jantjie in alternating roles), we meet them one Sunday morning at the top of his famous hillside painted rock garden.

The year is 1981, and by now the farm has become a well-known landmark for travellers on the way to the Kruger National Park and Swaziland. This is thanks to the bright patterns and shapes that Nukain has painted onto the koppie over the past two decades.

Aged and almost ready to go commune with his maker, there is only one surface left for him to complete. Referring to it as the “Big One”, it is the boulder that was always destined to be Nukain’s magnum opus.

Performed mainly in English - with elements of several other local languages spiced in-between - there are two major themes that run through Painted Rocks. And, it is at this point where Fugard reveals them in a very simple, yet staggeringly effective way.

The result makes for an experience that brims with the essence of why live theatre continues to remain unparalleled.

By physically including Bokkie in the painting of the boulder, the character becomes a vehicle for the viewer to gain insight both into Mabusa’s art, but also into the harsh reality that was his life.

Nukain tells Bokkie that certain lines represent the roads he’s had to walk hungry and barefoot on, for instance, or points out a shape referring to all those eyes who never saw him for anything other than a black labourer.

The fact that nothing’s changed for him is further demonstrated by the obtrusive arrival of the farmer’s wife, Elmarie Kleynhans (Van der Merwe). The change in atmosphere she brings, together with her actions and tone of voice towards both Nukain and Bokkie, is about to have life-changing repercussions.

After interval the viewer returns to the auditorium only to find that 22 years have passed.

Bokkie (Dladla), now a successful teacher, revisits the farm for the first time since that fateful Sunday. Against the faded backdrop of Nukain’s “Big One”, he runs into an elderly Elmarie, setting the stage for a traumatic reunion.

Designed by Saul Radomsky, during the second act the set effectively becomes a canvas representing current-day South Africa. Among the desaturated remains of what’s left of Nukain’s work, these characters get to express all their frustrations, fears and disappointments.

Radomsky once again delivers. It’s clear a lot of work and consideration went into creating this visually appealing playground for the performers, and a google search for photos of the real garden of flowers further reveals just how much research and effort was put into telling Mabusa’s story with authenticity.

The rest of the creative team is made up of Birrie le Roux (costumes), Mannie Manim (lighting design) and Charl-Johan Lingenfelder (sound design).

Fugard and Fourie’s tight-knit cast all rise to the challenge. Opting for a bold and dignified persona, Sebe’s Nukain has lots of presence and makes sure each of his character’s important words hit their mark.

True to form, Van der Merwe delivers the kind of performance that keeps her in demand. The strength of her portrayal lies in nuance. Nothing is exaggerated or done for effect alone, and as a result one eventually develops empathy for the hard-shelled Elmarie.

Over the past few years Dladla has established himself as force to be reckoned with in musical theatre. Thanks to Painted Rocks he gets to show his more serious acting chops as well, resulting in his strongest, most mature performance for me to date.

And then there is the 13 year-old Mango, who played the part of Bokkie on opening night. What a joy it was seeing him come into his own, both as a naturally gifted actor, but also one who is able to bounce comfortably within the boundaries set by his directors.

Entertaining, sobering, informative and educational, Painted Rocks ticks all the boxes of what important theatre should do. Above all, however, it makes us think of the countless individuals from our past whose names we’ll never even know.

The outsiders. The non-privileged ones. The unseen ones. The Nukain’s of South Africa’s faded landscape.

l 0861 915 8000