One woman’s mission: Raising boys to be good men

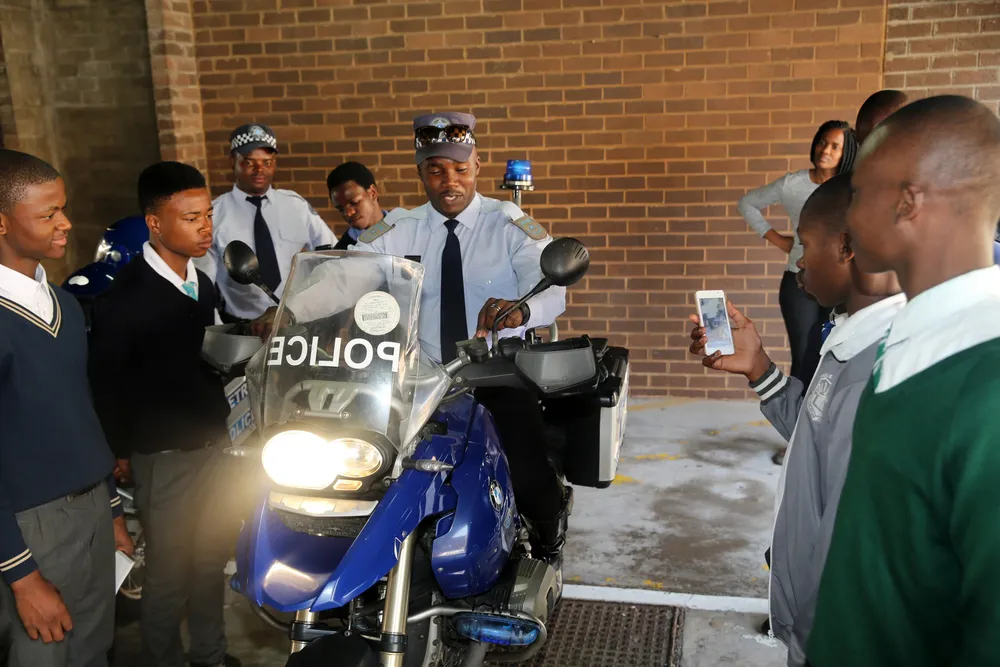

Take a boy child to work campaign- This is an expirience at the Fire arm rooms being tought of how to handle a fire arm carefully at the Metro police head quaters in Durban. PICTURE: Nqobile Mbonambi/ AFRICAN NEWS AGENCY (ANA)

Johannesburg - A single mother of a son now 21, she’s very passionate about the lot of the boy-child so much so that when she started work as chief executive officer of LoveLife, she took umbrage at the plethora of their programmes aimed at empowering the girl-child.

We need a boy-child programme, she kept saying. “All of your programmes are about girls. We need to change these focus points.”

Her concern about the plight of the boy-child her mantra: what about the boy-child? Subsequently, just last Tuesday, loveLife saw the project it co-sponsored come to life, the movie “What About the Boys?” hit came on circuit.

A Zimbabwean, Dr Linda Ncube-Nkomo; CA (SA), PhD, was widowed when her son was only 3 years old “and I decided we needed to come to South Africa”.

She spends a lot of her time – if she’s not at church – with her son. “I call him my universe. Pity that universe doesn’t want to spend time with me anymore.”

For Ncube-Nkomo the nuance in the conversations with boys is crucial. A simple greeting like “How are you?” would produce better results if it was rephrased to be: “How are you feeling?” “Because when you pose it like that, the answer is different. If you ask ‘how are you feeling’, we can then start talking about how you’re not feeling well, or are tired or whatever.

“We can then start unpacking your feelings. What happened that made you sad? How long have you been feeling sad? You’ve been feeling sad for too long now. We now need to find an intervention for you.”

This way of interacting with boys Ncube-Nkomo discovered when her son’s friends came over to visit: “I always noticed with my son that these kids don’t have safe spaces. They don’t have a place where they can talk about what they feel. So my home became that kind of place.”

“A lot of men have children and walk away. But that doesn’t mean the absence of a father is the end of the world. It requires of us, those who are left with the boy, to find other men, of strong moral compass, who we can bring into the lives of these young men. ”Whether it is the man next door because you’ve watched him through the years, and you’ve never seen him beat up his wife or raise his voice against her.

“You’re able to able to identify in your circle, men you can ask to mentor your boy. And those are the things we need to be talking about rather than lamenting the fact that such and such a percentage of boys are raised without fathers.”

The phenomenon of absent fathers cannot be wished away, she says: “It’s the reality, let us work with the men around us, so we can decide which ones can help with our boys.”

“I’m a single mom,” Ncube-Nkomo, reiterates. She says she had no idea how to raise a boy on her own, so she looked to her circle, the church, for help. “My circle was church groups. I got mentors for myself to raise my son. One woman, who was my mentor, shared with me the wisdom I’m sharing with you now: find men to help raise your son. They can never be the father of the child, but they could be the trusted uncle or older brother that the child can go to.”

You must be open with the men outside, she says. Tell them “this is what I’m struggling with, with my son”.

“The answers are there. We just need to stop waiting for someone to come do it for us, wait for the government. The government doesn’t raise children, we do – in our homes, in our communities.”

How do we raise boys not intimidated by their opposite number, the empowered girl child?

“Get them to understand their self-worth. In this world, no one is like me. We need to get our children to understand that they have value within themselves. Our journeys are different; our purposes are different. Once we get them to define life according to values, rather than according to things, we’ll start making progress.”

She makes it sound so easy to raise boys, most of whom without their fathers, tend to grow up troubled. She invokes Frederick Douglass: it is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.

This is not some pie in the sky notion, clearly. With her, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. It is in her she raised her boy, who she now goes on dates with “and he picks up the tab”. She does this to see “how he will treat a lady”.

A man of integrity, says Ncube-Nkomo, is one who can be trusted, who holds himself, and others, accountable.

Of the old dogs, Ncube-Nkomo says it is never too late to unlearn those things we learned.

Articulate and dynamic, she is in her element with the boy-child tale. “Why am I telling my son to go play outside and my daughter to stay indoors? What is it that he’s going to learn outside that I cannot teach him here? Surely he’s safer inside, with me.”

“Mothers are enablers of patriarchy. Why can’t her son wash dishes? He’s just eaten from those dishes!”

“We can raise someone, boy or girl, who can understand that life is competition, that life is about self-worth and from that I’m able to love another person. Once these foundations are in place, you’re then able to see me, your partner, as a person.”

Her chosen field as a Chartered Accountant is a male-dominated industry. She is glad she was raised by a feminist – her father.

The first of five children – four girls and a boy, she grew up to know that she could be anything she wanted, as long as she was good at it.

Now 50, she remembers conversations she had with her father while on a trip to buy school uniforms when she was only 7. “My Dad produced a wad of notes, and said ‘see this money, I’m spending this money so you can go to school’”.

“When I went into a male-dominated space, my colleagues were shocked to meet this outspoken woman who can answer back. I was raised to be confident. I never saw gender; never saw that as a limiter. You’ve got to learn to stand your ground. It also comes with age and experience. There are times when one thinks, ”I wish I could have used my voice better then.”

Engaged in 2017, she was then quickly disengaged. The talk was, she translates: “Women with PhDs are troublesome”.

She has seen women who could be shooting through the stars but have had to dim the lights so that their partners could feel accommodated. “I have to manage the dynamics at home, they say.”

But a man who has a high self-esteem can create safe spaces for women to fly. These are the kind of men Ncube-Nkomo is on a mission to build.

She summited Mount Kilimanjaro, a promise she made to herself at 40. She did this to buy menstrual products for the 3.5 million girls who miss out 50 days of schooling per year because of lack of sanitary pads.

She was part of the Trek4Mandela excursion.

“I love singing. That’s what recharges me. I was raised a Seventh Day Adventist. A lot of my time is spent at church. I also walk. I mentor young women. It is quite informal.”

But what she does best is raise boys to become good men. “My passion really is these boys. There are not enough voices talking about boys – and men. Not just in South Africa, but globally.”